Armies of Castile and Aragon 1370–1516

Osprey’s book on Castile and Aragon is really more about Trastamara rule, with Enrique II taking the throne of Castile in 1369 and the Hapsburg Charles II taking over Spain in 1516.

Osprey’s book on Castile and Aragon is really more about Trastamara rule, with Enrique II taking the throne of Castile in 1369 and the Hapsburg Charles II taking over Spain in 1516.

The beginning of this tale is familiar to many English-language history buffs, as it crosses over with the Hundred Years War. After that, not a lot of attention is paid until 1492 and the surrender of Granada allows for funding overseas adventures. As usual, there’s a good three-page chronology at the start to help place everything.

The Weaponry & Tactics section is brief, but introduces the important points, including vulnerability to English armies. This is best known for the battle of Nájera, but lesser known is the battle of Aljubarrota, where Juan I Trastamara tried pressing a claim to Portugal and was defeated by a smaller force with plenty of English and Gascon veterans in it. Unfortunately, there’s little follow-up to this section, including how Iberian organization and tactics changed (or failed to) after this, though in the short term Juan refused any more set piece battles with English troops.

There’s a good couple of pages about sea power in the two kingdoms, a subject that hardly ever gets enough attention in this era. From there, we get a history of the campaigns from 1407-1444, which is mostly the Aragonese expansion into Sicily and Italy. This is also informative, if predictably a bit confusing (we are talking Italian politics here), especially as we get to see how the two areas tie together.

After that is a major section on the consolidation of Castile and Aragon, and of course the conquest of Granada. That section in particular was eye-opening, as it was logistically extremely difficult country, and the war was quite extended by the difficulties in campaigning there. The book then finishes up with further campaigning in Italy at the end of the Fifteenth Century.

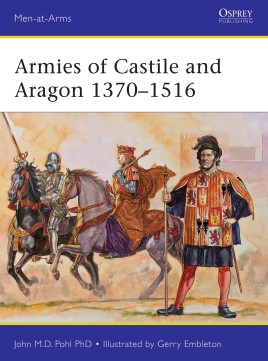

This is much more of a ‘pocket history’ than the examination of the armies that the Men-At-Arms series is technically supposed to be. As such, it’s well-written and informative, but doesn’t really give much idea of what these campaigns might have looked like. Similarly, Gary Embleton’s color plates are decent, but nothing special. That said the plate descriptions are good, and there’s the usual plethora of photos of period artifacts, and art (all black-and-white this time, which is becoming less common in the series).

Discussion ¬